Menagier de Paris is my absolute favourite book of household management. It was written I the late 14th C, in French, and has much practical information and many recipes. The references here are from the version “The Good Wife’s Guide” translated by Gina L. Greco and Christine M. Rose (Cornell University Press, 2009).

On page 257, in a section on dinners and suppers for great lords and others, we have

28. Dinner for a meat day served in 31 dishes and 6 courses:

First course. Grenache wine with sops of toasted bread, veal pasties [166], pimpernel pasties, boudin [6], and sausages [353].

and

29. Another meat dinner of 24 dishes in six course:

First course. Pasties of veal minced will with beef fat and marrow, pimpernel pasties, boudin, sausages, pipefarces [264], and small Norse pasties [258] de quibus.

On page 271, we have recipe 6.

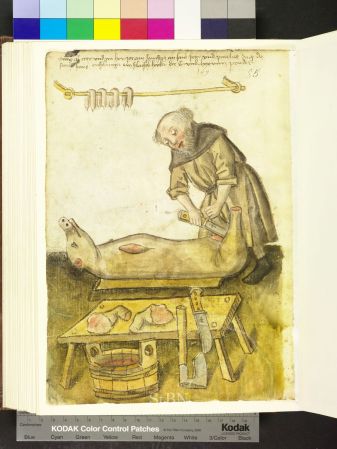

“Item, to make boudin (blood sausage), collect the blood of a pig in a suitable basin or pan. When the pig has been butchered and the haslet (pork viscera) washed thoroughly and set to cook, while it is cooking, remove the clots of blood from the bottom of the basin and discard them. Next, mix peeled and minced onions, about half the amount as there is blood, with abut half as much entrecerele – that is, the fat found between the intestines – minced as small as dice. Add some ground salt, and stir the mixture into the blood. Grind together ginger, cloves, and a little pepper. Take the small intestines, wash them well, turn them inside out, and rinse well in running water. To remove the odor, place them in a pan on the fire and stir; then add salt, and do it a second and a 3rd time and then wash them. Turn them, this time outer side out, wash them, and set them to dry on a towel, rubbing and wringing them to remove moisture. (What are called the entrecrele are the large intestines, which have fat inside that is pulled out with a knife.) After you have measured and put in equal portions and quantities (half as much onions as blood and a quarter as much fat), and when your boudins (the intestines are used as sausage casings) have been filled with this mixture, cook them in a pan with the haslet broth, and prick them with a pin when they swell; otherwise they will burst. Nota that the blook keeps well for two, indeed even 3, days, once the spices are added. Some may use as spices pennyroyal, savory, hyssop, and marjoram, gathered when they are in flower and then dried and ground. As for the haslet, put it in a copper pot to cook on the fire, whole and without salt, and skim the pot along the edges, for haslet will foam. When it is cooked, take it out and save it to make pottage.

To make liver boudin. Take two pieces of liver, two pieces of lung, a piece of fat and put it in an intestine along with some blood, and for the rest do as above.

Nota that good boudin can be made with goose blood, provided that the goose is thin, for thin geese have larger intestines than fat ones.

Queritur: How are intestines turned inside out to be washed? Responsio: by a linen thread and a brass wire as long as a gauger’s (weights and measures official) rod.

7. Nota that some folks hang their pigs during the Easter season and the air yellows them; for this reason it is best to keep them in salt as they do in Picardy, although it seems that the flesh is then not as firm. Nonetheless, it is much nicer to serve fair and white lard than yellow, for no matter how good the yellow is, its unappealing color condemns it and discourages its use.

8. To make Andouille sausage. Nota that Andouille sausages are made from rectal guts and other large intestines, which are stuffed full of the other entrails to make sausage. These small intestines, when you want to put them in Andouille sausages, are split lengthwise into 4 parts. Item, you can make Andouille from thinly sliced stomach. Item, from the meat beneath the ribs. Item, from sweetbreads and other things that are around the “small haste” (spleen) when you do not wish to use the small haste intact. But first these entrails are deodorized in a pot with salty two or three times, as described above for boudin. The other things explained above, that is, the lower and other guts that must be filled to make Andouille sausage, are first pricked and sprinkled with a half ounce of powdered pepper and a sixth of fennel, ground, with a dash of finely ground salt sparingly added to the spices. When each Andouille is thus stuffed and filled, you place them to be preserved in salt with lard, on top of the lard.”

This section is followed by a long section naming and describing the parts of various butchered animals, and their costs, as well as instructions for salting and preparing hams. Recipe 8 looks quite a lot like Platina’s Lucanian sausage in his 1475 cookbook.

On page 278, there is a recipe for White porée. “50. White porée is so named because it is made from the white of leeks, pork chine, andouille or ham, in autumn or winter for a meat day. Understand that no other fat besides pork tastes right in it. First, you select, mince, wash, and blanch the leeks – that is, in summertime when the leeks are young, but in the winter when the leeks are older and tougher, they should be boiled instead of just blanched. …Likewise, cook minced onions and then fry them. Next, fry the leeks with those onions, then mix together to stew in a pot, with cow’s milk if it is a meat day. … If it is a meat day, when the leeks are blanched in summer, or boiled in the winter, as explained, set them to cook in a pot of salted meat or pork stock and add lard. Nota, this leek porée is sometimes thickened with bread.”

On page 280, at the end of a long section on cabbage identification, cultivation, and cooking, we find “If you prepare cabbage on a fish day, boil it, cook it in warm water, and add oil and salt. Item, some add meal. Item, instead of oil, some put butter in. On a meat day you might add pigeons, sausages and hare, coots and plenty of bacon.”

On page 287, there is a recipe for “Broth of pork tripe. Grind some ginger, cloves, grain of paradise, etc., then mix with vinegar and wine. Take some toasted bread that has been soaked in vinegar, grind it, strain and mix all together. Then cut the viscera in pieces and fry them in lard. Pour stock of boudin or offal into a pot along with the bread and spice mixture, and boil. Add the pieces of fried viscera, bring to a boil once, and serve.”

On page 317, there are recipes for both summer Andouille and meatballs (also frog’s legs, but that’s a whole separate issue).

“254. Summer Andouille. Take the tripe of a lamb or kid and remove the membrane, cook the remainder in water with a little salt, and when it is cooked, mince it finely or grind it. Beat 6 egg yolks and a tablespoon of fine powdered spices together in a bowl; then add and mix in the tripe. Next, spread it all on the intestinal membrane and roll up as for sausages. Tie loosely with thread lengthwise and then tightly crosswise; and then roast on the grill. Remove the thread before serving. Vel sic (or this way): make into balls, that is, using the membrane itself, and fry these balls in lard.

255. Meatballs. Take lean meat from a raw leg of mutton and the same from a lean pork leg. Chip it all together finely, then in a mortar grind ginger, grains of paradise, clove, and sprinkle this over the ground chopped meat. Mix in some egg white, but no yolk. Using the palms of your hands, form the raw meat and spices into the shape of apples. When the mix is all well shaped, cook them in water with some salt. When done, remove them and spit them on skewers of hazelnut branches to roast. As they start to brown, have ready some ground and sieved parsley mixed together with four, neither too thinly nor too thickly. Take the meatballs off the fire and put a dish under them, and holding the spit over the dish, turn it and coat the balls well. Put them back over the fire as many times as needed for them to turn quite green.”

That last sentence always makes me giggle, as I associate meatballs turning green with something quite unpleasant. This phrase is awkward in several ways!

The last mention of sausage in Menagier comes in recipe 353, on page 336: “To make sausages after killing a pig. Take some meat and chops, first from the part they call the filet and then from another area, and some of the finest fat, as much of one as the other, in the amount for the number of sausages you want. Have this finely ground and chopped by a pastry cook. Then grind fennel and a little fine salt. Next, thoroughly mix the fennel with a quarter as much of powdered spices. Combine well the meat, spices, and fennel. Fill the intestines, that is, the small intestines, with this mixture. Know that the guts of an old pig are better than those of a young pig because they are larger. After this, smoke them for four days or more. To eat them, bring once to a boil in hot water and then grill.”

The key bit of information for me in this recipe is that I don’t have to chop all the meat myself. I have a manual meat grinder, and access to an electric meat grinder but had figured that I should do at least some of my sausages by chopping the meat with a knife. I will still do that, but I feel much better knowing that 14th C Parisian housewives didn’t have to do all that work, so I can use my grinder for most of the sausages.

Read Full Post »

This was a fairly popular image, as you can see from this mid-1200’s detail in a Belgian psalter by an unknown illuminator (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 14, fol)

This was a fairly popular image, as you can see from this mid-1200’s detail in a Belgian psalter by an unknown illuminator (The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 14, fol)

For a much later picture of enjoyment of the fire, and sausages, we have Pieter Aertsen’s 1560s oil painting on wood, found in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp. Note the sausage on the ground in the bottom left corner. According to the Web Gallery of Art “The scene has all the elements of a rural booze-up. Much drink is being consumed, sausages grilled and bacon fried. There are festive biscuits on the table and a tray of waffles. Crowns like the one worn by the boy were used on the Feast of Epiphany, but also during other winter festivities, including Shrove Tuesday. Neither holiday is being celebrated here, however. The bird-cage next to the door on the left tells us that the scene is taking place in a house of ill repute, such as a tavern or brothel. Other elements combine to suggest the latter – the way the young man places his arm around the girl’s waist, the copious eating and drinking, the aggression symbolized by the man with the two weapons, and the foolishness reflected by the king’s crown.”

For a much later picture of enjoyment of the fire, and sausages, we have Pieter Aertsen’s 1560s oil painting on wood, found in the Museum Mayer van den Bergh, Antwerp. Note the sausage on the ground in the bottom left corner. According to the Web Gallery of Art “The scene has all the elements of a rural booze-up. Much drink is being consumed, sausages grilled and bacon fried. There are festive biscuits on the table and a tray of waffles. Crowns like the one worn by the boy were used on the Feast of Epiphany, but also during other winter festivities, including Shrove Tuesday. Neither holiday is being celebrated here, however. The bird-cage next to the door on the left tells us that the scene is taking place in a house of ill repute, such as a tavern or brothel. Other elements combine to suggest the latter – the way the young man places his arm around the girl’s waist, the copious eating and drinking, the aggression symbolized by the man with the two weapons, and the foolishness reflected by the king’s crown.”